The Only Woman At Red Beach

As Marines climbed aboard their landing craft at Inchon, one woman, a reporter for the New York Herald Tribune, went with them. She was the only female to land at Red Beach on September 15, 1950. She covered the invasion with up-close, graphic, and oftentimes tragic stories of courage and self-sacrifice.

From Inchon to Seoul to Chosin and finally Hungnam, the 30-year-old journalist spent six months in Korea. Her name is Marguerite “Maggie” Higgins.

A Woman In A "Man's Profession"

Born in 1920 in Hong Kong, Marguerite was destined for a life of adventure and travel. Her father, an Irish-American who had served as a World War I pilot and married a French woman, settled in Hong Kong for business reasons. The couple’s first and only child, Marguerite, was born a year later. By the age of twelve, Marguerite, or Maggie as she was affectionately called, spoke fluent French and Chinese.

She graduated from UC-Berkeley in 1941 and later earned a master’s degree in journalism from Columbia University. She was soon working for the New York Herald Tribune where she hoped to persuade her boss to send her to Europe.

By 1944, her perseverance had paid off. Despite being a woman in a "man’s profession," she was sent to Germany and joined a US Army unit fighting its way to Berlin. She was one of two American reporters to enter Dachau concentration camp on April 29, 1945, as American GI’s liberated its prisoners. What she saw made a lasting impact on her. During her time covering the war, she witnessed some of the most historic events of the 20th century.

Five years later she was reporting from the front lines of Korea. Ms. Higgins, the Tribune’s Tokyo bureau chief at the time, was sent to Seoul just two days after North Korea’s invasion of South Korea on June 25, 1950. The most memorable and demanding period of her life had begun.

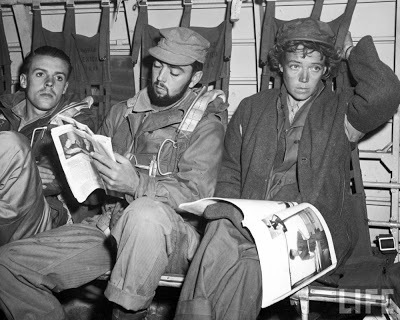

Marguerite Higgins with General MacArthur in Korea, 1950. (Photo credit Life Magazine)

Maggie Eats, Sleeps, And Fights Like The Rest Of Us

Maggie spent the next six months on the war-ravaged Korean peninsula, reporting on nearly every major US military operation. Her ability to endure sleepless nights, minimal food, and constant danger earned her the respect of the GI's she met. One Army officer remarked, “We’ve learned Maggie will eat, sleep, and fight like the rest of us, and that’s a ticket to our outfit any day.”

The feeling was mutual. Ms. Higgins' deep respect and admiration for the young men struggling to fight and win a war many Americans were not interested in made her a tireless advocate of the common infantryman, or “grunt,” on the ground. She became their greatest champion and was determined to tell their remarkable, heroic, and often heartbreaking stories.

She became so attached to the men on the front lines that she frequently risked her life to tell the “real” story of the war, the story of the average soldier and Marine. Many of her colleagues said she was reckless and foolhardy, but regardless of the criticism, she never relented.

With The Marines At Red Beach

In one of the most dangerous moments of her life, she landed with the Marines at Red Beach, a “rough, vertical pile of stones,” and climbed over a seawall with “improvised landing ladders topped with steel hooks.” Within seconds, North Korean troops were pounding the Marines with “small arms and mortar fire,” even throwing “hand grenades down at us as we crouched in trenches.” Despite the danger, Maggie was with “her” Marines and felt confident.

Marines storm ashore at Red Beach in this iconic picture of the Inchon Landing. (Photo credit USMC)

She would stay with the First Marine Division through the liberation of Seoul and later join them at Chosin.

Her front-page Herald Tribune articles were read by millions, and her uncensored, often disturbing stories of refugees and GI’s dying in Korea, a country many Americans had little interest in, shocked the nation. Within months of returning to the States, she became the first woman to be awarded a Pulitzer Prize for international journalism.

Higgins' time in Korea proved she was a war correspondent as good as any man.

On this, the 68th anniversary of the Inchon Landing, we pay tribute to Maguerite Higgins, a courageous reporter who risked her life at Red Beach, and throughout the Korean peninsula, to tell the stories of the young men who fought, sacrificed, and died to keep Korea free.

We will always remember.

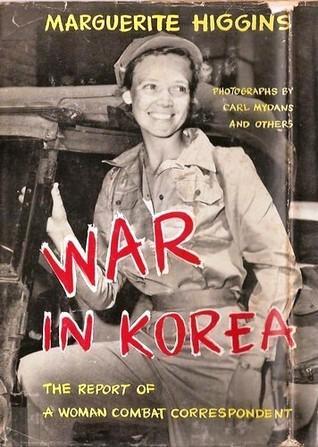

Top/Feature picture: Maggie Higgins in Korea (Photo credit: Time Magazine)

Marguerite Higgins, student at Macalester College in St. Paul.Minnesota.

Founded in 1874, The college has Scottish roots and emphasizes internationalism and multiculturalism.

- first woman to win a Pulitzer Prize for Foreign Correspondence

- advanced the cause of equal access for female war correspondents

Marguerite Higgins

Marguerite Higgins Hall [mὰːrgəríːt híginz hɔːl]

Marguerite Higgins Hall (September 3, 1920 – January 3, 1966) was an American reporter and war correspondent.

Higgins covered World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War, and in the process advanced the cause of equal access for female war correspondents. She had a long career with the New York Herald Tribune (1942–1963), and later, as a syndicated columnist for Newsday (1963–1965).

She was the first woman to win a Pulitzer Prize for Foreign Correspondence awarded in 1951 for her coverage of the Korean War.

Early life and education

Higgins was born on September 3, 1920, in Hong Kong, where her father, Lawrence Higgins, was working at a shipping company. Her father, an Irish-American, met his future wife and Higgins' mother, Marguerite de Godard Higgins (who was of French aristocratic descent) in WWI Paris. Shortly afterward, they moved to Hong Kong, where their daughter was born.

The family moved back to the United States three years later and settled in Oakland. Higgins' father lost his job during the 1929 stock market crash, which promoted anxiety for the family. In her autobiography, News is a Singular Thing, Higgins wrote that it was the worst day of her childhood:

"It was on that day that I began worrying about how I'd earn a living when I grew up. I was then eight years old. Like millions of others brought up in the thirties, I was haunted by the fear that there might be no place for me in our society."

Regardless, the family managed to get by. Higgins' father eventually got a job at a bank and her mother was able to get Higgins a scholarship to the Anna Head School in Berkeley, in exchange for taking a position as a French teacher.

University of California, Berkeley

Higgins started at the University of California, Berkeley, in the fall of 1937, where she was a member of the Gamma Phi Beta sorority and wrote for The Daily Californian, serving as an editor in 1940.

After graduating from Berkeley in 1941 with a B.A. in French, she headed to New York with a single suitcase and seven dollars in her pocket with the intent of getting a newspaper job. She planned to give herself a year to find a job, and if that failed, she would return to California to be a French teacher. Having arrived in late summer, she applied to the master's program at the Columbia University School of Journalism.

Columbia University

She walked into the New York Herald Tribune city office after arriving in New York in August 1941. She met with the city editor at the time, L.L. "Engel" Engelking, and showed him her clippings. While he didn't offer her a job at the time, he told her to come back in a month and maybe he'd have a position for her. She decided to stay in New York and studied at Columbia.

While at Columbia, she had to fight her way in. Having tried to get in just days before the program began, the university said that all the slots allotted to women were filled. After multiple pleadings and meetings, the university said they would consider her if she was able to get all her transcripts and five letters of recommendations from her previous professors.

Instantly, she got on the phone to call her father to arrange for all the materials from Berkeley to be sent to Columbia. A student dropped out of the program right before the first day and Higgins was in.

Upset that the coveted campus correspondent for the New York Herald Tribune had been filled by her classmate Murray Morgan, she did her best to outdo her classmates, most of them men. According to one of her professors, John Tebbel, her beauty matched her brains, being one of the best of her class:

"Even in a class full of stars, she stood out. Maggie was positively dazzling, with a blonde beauty that hardly concealed her equally dazzling intelligence. She was all hard-edged ambition. In those days women had to be tougher to succeed in journalism, a male-dominated and essentially chauvinistic business, and Maggie carried toughness to the outer edge, propelled by driving ambition, which was soon apparent to us all."

In 1942, Higgins replaced her classmate as the campus correspondent for the Tribune, which led to a full-time reporting position.

'Beautiful People' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 이승만의 ‘독립정신,’ 주사파의 ‘좀비 정신’ (0) | 2024.05.05 |

|---|---|

| [조국의 하늘을 날다] - 김신 (0) | 2024.05.05 |

| Marguerite Higgins Hall- 1st woman to win a Pulitzer Prizes (0) | 2024.05.05 |

| Most-beautiful-women-in-history (0) | 2024.05.05 |

| Top 10 Most Romantic Nationalities in The World (0) | 2024.05.05 |